All this month I am writing about the jaw dropping Indian handlooms, a quick but captivating dive into the saree specifically, a garment worn by Indians for five millennia. Come with me into the amazing, complex and utterly fascinating world of fibre and yarn, of skills and techniques of dyeing and printing and embroidery, traditions unchanged for centuries. Of sumptuous finished fabrics that not only make a fashion statement, but also constitute our cultural heritage and political identity.

J is for Jehangir, Jama and Jamdani

Remember Jehangir? He was the Mughal Emperor who, in 1608, granted the British East India Company the first trading licence to set up a 'factory' (trading station) in India. At the time, the Mughal Empire was well established, Jehangir's great grandfather Babur, a descendant of Tamurlane and Genghis Khan, had landed up in India in the 1520s, and Jehangir's father Akbar had expanded and consolidated the Empire. Jehangir himself was a great patron of arts and culture and every art and industry, including textiles, flourished under him and his fashion forward consort Nur Jahan.

The Mughals had brought with them a swathe of Islamic religio-cultural influences from their original homeland, part of the Persian Empire, and they'd happily meshed it with the traditional richness of the millennia old Indian civilisation. In fact, very few imperial dynasties have had the artistic astuteness and refined aesthetics that the Mughals possessed, expressed with a striking consistency through architecture, literature, libraries, music, painting, calligraphy, food, and of course, last but not the least, jewellery and apparel. (It's telling that the word 'mogul' has entered the English language and continues to mean a powerful person of great importance/influence.)

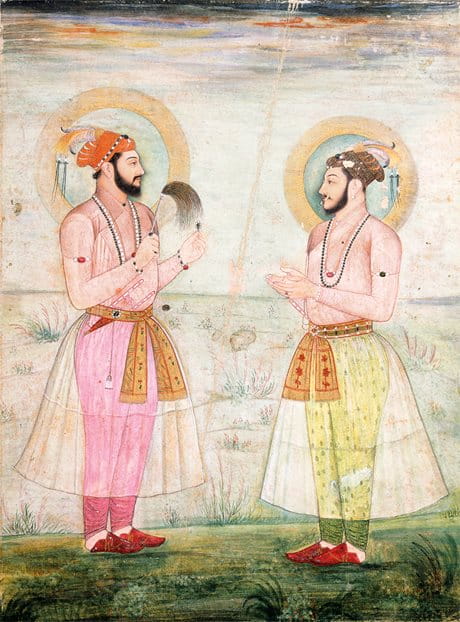

The first reference we have to Jamdani weaving is a sash around Jehangir's waist in a 17th century painting. The word 'Jamdani' is of Persian origin comprised of two separate words meaning 'flower' and 'container.'

The gossamer fine cloth with these striking motifs has always been associated with Bengal, with Dhaka which is now in Bangladesh. Dhaka's history goes back to around the 6th century and it has been the traditional centre of handloom weaving. Xuan Tsang, a Chinese traveller to India (629-45 CE) compared the fabrics woven there to 'light vapours of dawn.' Arab traders have referenced these superbly delicate cotton handlooms in the 9th century as 'fine enough to pass through a signet ring.' Poets of the Mughal court called them 'baft hawa' or woven winds, 'abrawan' - flowing waters and 'shabnam' - evening dew, all lyrical names highlighting their lightness and transparency. Akbar, Jehangir's father, had reserved the finest, most transparent and delicate of these fabrics solely for royal use. This fabric came to be known in the West as Muslin. Jamdani was a flowered muslin, considered to be one of the most complex and advanced handloom weaving art.

|

| Motifs on a W. Bengal Jamdani handloom cotton sari. |

In the 18th century, the Muslin industry was lost as the EIC systematically destroyed the Indian textile industry. But mercifully Dhakai Jamdani weaving survived and was declared an intangible cultural heritage of Bangladesh by UNESCO in 2013.

|

| Image source. Mughal princes in Muslin 'jama' a long coat/robe. Note the original sheerness. |

What exactly is Jamdani weaving? It is a discontinuous weft technique, where a special tool called a 'Kandul' is used to inlay motifs into the weft of the fabric as it it being woven, so that the sheerness or weight of the fabric is not affected. It is considered to be the most advanced, complicated handloom weaving technique, demanding a high level of skill and knowledge. Watch this video to see how a jamdani saree is woven:

Originally, jamdani sarees were woven in a cluster around Dhaka. Some weavers migrated to weaving hubs near Calcutta and brought jamdani weaving to other parts of Bengal. Today jamdani weaving is done not just in Bengal but also in several other parts in the North, South and Central parts of India. Read more about Indian Jamdani weaving here and here.

|

| Jamdani from India. These motifs are not embroidered or printed on the fabric, but woven into the weft simultaneously by employing an extra, special tool. |

|

| Detail of a motif. Front view. |

|

| Detail of motif. Back view. |

Note

how the yarn making the pattern is woven into the weft and finished without any

loose ends. Also, the pattern isn't traced anywhere on the fabric, in fact

there is no fabric to trace patterns on, as only the warp yarns are fixed on

the loom as weaving begins. Sometimes, the more complicated jamdani patterns

are drawn on a template or graph paper and held below the fabric as it is

woven. Often, the master weavers weave without any patterns at all, relying on

experience and the cumulative knowledge/skills handed down for many

generations.

J is for Jeopardy

...which is what the entire Indian handloom sector is in - because of cheaper machine made substitutes and the lack of interest on the part of the younger generations. Read about some of the challenges the weavers face here.

~~~

Everyone knows about Ancient Rome's fascination for Indian textiles, but did you know that Indian handlooms once travelled East as well, to Japan? In the 17th century, Indian textiles were popular in Edo, the former name of Tokyo. Even today, Japan remains a significant importer of Indian handloom goods. There are Japanese enterprises which collaborate to keep these historical ties alive. Read about one of them here.

Thank you for reading. And happy A-Zing to you if you are participating in the challenge.

Amazing. Just amazing.

ReplyDeleteExquisite. I so hope it continues to survive. And indeed thrive.

ReplyDeleteHari OM

ReplyDeleteBeautiful! YAM xx

Oh wow, the sheerness in the painting is fascinating. I would love to see a reconstruction of those outfits...

ReplyDeleteThe Multicolored Diary