All this month I am writing about

vibrant Indian handlooms, a quick but captivating dive into the saree

specifically, a garment worn by Indians for five millennia. Come with me

into the magnificent, complex and utterly fascinating world of fibre and yarn,

of skills and techniques of dyeing and printing and embroidery, traditions

unchanged for centuries. Of sumptuous finished fabrics that not only make a

fashion statement, but also constitute our cultural heritage and political

identity.

V is for Vegetable

Before

we get into the main topic, I'd just like to mention Venkatagiri sarees. These

are woven in Andhra Pradesh, with a history going back to the 1700s. Read about

these sarees here and/or watch a short video about them below:

There's

also the Valkalam saree, but we'll visit that in a later post. It is

a saree from the super ancient weaving hub of Benaras or Varanasi, which needs time

and a bit of elaboration to do it justice. Can't do that here.

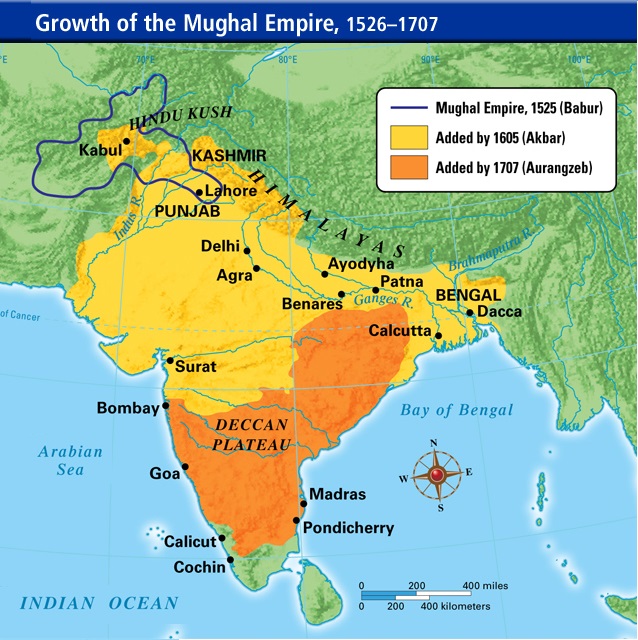

Incidentally, Vijayanagar was a Hindu Empire that lasted for two centuries (1336-1565) and was an important historical milestone in South India. Though geographically much smaller and of shorter duration than the Mughal Empire in the North, it left a similar cultural legacy in literature, architecture and art of the southern region. It had a roaring trade in textiles, woven in centres like Coimbatore, Mysore and Pulicat.

|

| Image credit |

And here is the Mughal Empire as a quick comparison -

|

| Image credit |

Right,

that's enough already. Let's get into the main topic for today - vegetable

dyes.

Like everything textile-related, the roots of the vibrant colours of Indian textiles, pardon the pun, goes back to the Valley. The Indus Valley. Dye vats and fragments of madder-dyed cotton wrapped around a silver pot have been found in Mohenjo-Daro, it shows an advanced level of knowledge of mordant dyeing and colour fixing. Similarly, the Priest-king we saw at the start of the series wears what is believed widely to be a madder dyed textile robe. Artisans knew the use of madder and indigo to obtain vivid red and blue for textile dyeing four/five thousand years ago. In fact for long centuries Indian red and blue were kind of colour monopolies in the textile trade. Not just that, they had precise knowledge and control of the dyeing process to get a range of shades from 'dawn flushed' as mentioned in a Chinese text in the 7th century, to deep, intense reds and blues. Banabhatta, a poet and writer from Kanyakubja (modern day Kannauj, UP) mentions costly tie and dyed textiles in various designs, also in the 7th century. A French traveller in the 18th century mentions the colour fastness of Indian textiles that lasted the entire life of the garments. In short, there is no dearth of evidence on the knowledge and skillfulness of Indian textile artisans regarding colours/dyes.

The Indus Valley Civilisation vanished by 1500-1400 BCE, there's no tangible archaeological record for a few centuries within India itself. However, the Greek historian and physician Ctesian mentions brightly coloured cotton from India in the 5th century BCE. Ctesian was the court physician in the Persian Empire at the time, known for his texts Persica and Indica - these show that Indian textiles continued to be exported to Persia during the 1st millennium BCE even after the collapse of the IVC and the rise of newer dynasties and empires. This trade in Indian textiles continued and expanded to progressively include Greece, Rome and rest of Europe, as well as the New World, right through to the 18th century, when the Industrial Revolution and discriminatory colonial policies brought Indian trade supremacy to an end.

Natural dyes can be classified into three broad types - vegetable, animal and mineral - according to their source. Another broad classification can be as per their application techniques - vat dyes, mordant dyes and direct dyes. Vat dyes are those which are insoluble in water but become soluble when treated with a reducing agent, i.e. they require 'vatting.' Mordant dyes are those that require a binder, usually a metal salt, to adhere to the fabric. Direct dyes, as the name implies, are dyes that can be applied straight to the textiles. The most common mordant used was alum and iron sulphate. Other mordants were also known but they were extremely toxic and impact both the artisans and the environment and so have been discontinued in modern times. Many dyes and also mordants are malodorous therefore dyeing communities tended to operate in separate enclaves outside the main towns.

Dyeing can be done on fibre itself before spinning ('dyed in the wool'), after spinning or 'yarn-dyed' and after weaving that is 'piece dyed.' Indian sarees use both the latter processes extensively. For example, Batik and Ajrakh sarees are printed as pieces, while most Kanchipuram and Ikat sarees are woven after dyeing the yarn.

Some of the more important vegetable dyes that Indian artisans used were Indigo (blue), Madder (red , burgundy and lilac), Turmeric (yellow), Saffron (orange to yellow) Safflower, Parrot tree flowers and Pomegranate. Read more about Indian dyes used here and here.

Synthetic dyes were developed in mid-19th century and changed the textile industry - natural dyes were replaced by their synthetic counterparts. These were easier and quicker to produce on a mass scale, and unlike natural dyes, could be used for manmade fibres/fabrics as well. Note that the first man made fibres happened to be created in the 19th century too.

In recent times, there is a movement towards the use of natural dyes as the negative environmental impact of chemical dyes have become apparent and consumer consciousness about health and sustainable practices has grown.

Watch this short film on the history of Indian natural dyes below. Vibrant coloured textiles remain a part of life in modern India and continue to play an important role in traditional attires of both men and women.

~~~

Did you know that lac is a natural dye? - it's obtained from insect resin and used to dye textiles. It yields colours ranging from crimson to burgundy red and deep purple.

Thank you for reading. And happy A-Zing to you for the end days of the challenge if you are participating.

Amazing colors from such a variety of vegetables. It's all so much work - excellent post. I'm not the biggest veggie eater, so happy to donate my share to the beauty of the sarees and other textiles.

ReplyDeleteI am loving this series and continue to learn. Megathanks.

ReplyDeleteHari Om

ReplyDeleteAgain I add my thanks for your efforts in bringing the history and mystery of the industry to us! YAM xx

The little videos are so helpful in a deeper understanding of all the processes you mentioned during your A to Z.

ReplyDelete