Untangle your headphones today for a marathon Bengali folk music session.

First, here is a folk band called the Folk Diaryz with Golemale Golemale Pirit Koro Na, presented by Folk Studio Bangla.

Much of our folk music has been 'repurposed' in recent years to appeal to the more globalised Bengali taste, younger, more demanding, more fickle, and more exposed to Western orchestra style accompaniments.

Purists of course argue that Bengali folk is not meant to be accompanied elaborately - an ektara/dotara (lit one-stringed/two-stringed) and a pair of cymbals or a special pointed drum were traditional, even a cappella. Others lament the loss of the robustness of the dialects/regional pronunciation which become unnecessarily refined and urbanised in these modernised versions. But I am okay with the newer singers mixing and matching instruments and the urbanised, 'softer' pronunciations. The songs live on - that's the most important thing.

The next one is a band called Fakira with a track called Bhromor Koiyo Giya (Oh Bee, Go Tell...). That's followed by Tomay Hrid Majhare Rakhibo (I'll keep you centre-heart) by Lopamudra Mitra.

The next one is a band called Fakira with a track called Bhromor Koiyo Giya (Oh Bee, Go Tell...). That's followed by Tomay Hrid Majhare Rakhibo (I'll keep you centre-heart) by Lopamudra Mitra.

Every generation reinvents its music to suit its own taste, that's how it should be, otherwise the songs which have come down through centuries, would be lost, and that would be a true shame. There's no shame in a keyboard or guitar being played with a folk song. Though I have to say I'm fossilised enough myself to like the traditional formats also.Here's the last song from Folk Band Proyas, Manob Jonom, written and composed by Fakir Lalon Shah.

And finally I have for you a different style and a vibe that's contemporary as compared to the timeless ones above - the football song Friendship Chai (Want friendship) by the very popular band Fossils. Bengalis are somewhat football-mad and of course as cricket-crazy as the rest of India.

Flick...Formula...n...Friction

It

irks me not a little that the term ‘Indian film’ has come to be synonymous with

Bollywood. Bollywood is undeniably a great mass entertainer, it

produces more than 800 films annually, double that of Hollywood, its closest

global counterpart. Many of those formula films are viewed worldwide because

they are easy on the eye - slick sets, simplistic storylines, lots of music and

dance, melodramatic acting - generally totally divorced from reality. They are nice

to relax with after a hard day when you don’t want to strain the brain.

But

they are not the only films that are made in India. There is a strong tradition

of regional films in other parts of India, including West Bengal, dating back

to the first decades of Indian cinema. The Bengali film industry, located in a Calcutta

neighbourhood called Tollygunge, has been known as Tollywood since 1930’s. It

has always produced a fraction of the output of Bollywood, but the films have

been far more nuanced, of varied genre and wide-ranging themes, and technically

innovative.

The

first ‘bioscope’ show was screened in Calcutta in 1897, within two years of the

first commercial screening in a Paris café. The first chain of Indian cinemas,

Madan Theatres, was owned by a Parsi theatre/film magnate, J.F.Madan, who

set up the Elphinstone Bioscope Co in 1905. Elphinstone formally merged with

Madan Theatres in 1919. It produced the first silent Bengali remake in Calcutta

– Satyavadi Raja Harishchandra in 1917, followed by the first Bengali feature -

Bilwamangal in 1919.

Silent

films gave way to the ‘talkies’ and the first Bengali ones, Jamai Shashthi and

Dena Paona were released in 1931. More than 50 Bengali films were produced in

the years till 1947, when India became independent. This growth was underpinned

by Bengal’s unusually rich literature, with many well-loved literary gems being

adapted for the silver screen.

In

the fifties, three young thirtysomething directors burst upon the Bengali cine

screens and changed film making forever. And one of them made his impact felt not

just in Bengal but across the world. The trio of Ritwik Ghatak-Mrinal

Sen-Satyajit Ray created classics and cinematic milestones, spearheading the

parallel cinema movement in Bengal. They portrayed social realities with a

spare perspective and clear eyed nuance quite removed from the more

melodramatic offerings of Bollywood.

Ray

was a polymath – a graphic artist, music composer, cinematographer,

calligrapher, science fiction, crime fiction and children’s writer, script-writer,

editor, designer, illustrator, and also a giant among filmmakers everywhere. He

won accolades nationally and internationally in his 40-year career and multiple

awards at Venice, Cannes and Berlin film festivals, ending with an honorary Oscar

from the American Academy and the Padma Bhushan just before his death in 1992. His first feature film

– The Song of the Little Road (Pather Panchali) is an acknowledged cine classic

lauded by his contemporaries like Akira Kurosawa and by directors who came

after him such as Martin Scorsese. He made some 35-40 films, mostly black and

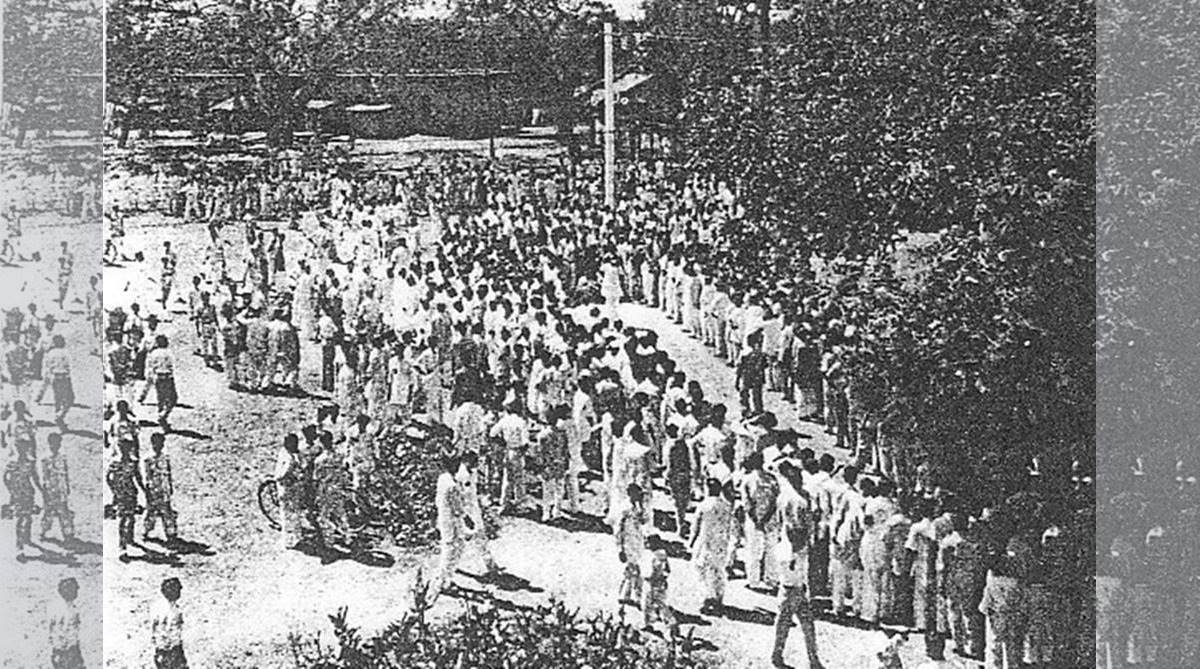

white - each one is worth watching. When he passed away, the entire city of

Calcutta came to a virtual standstill. The next day, April 24th

1992, the New York Times headline read Satyajit Ray, 70, Cinematic Poet,

dies.

Ritwik Ghatak is less well known outside Bengal, but totally should be. Ghatak came to film-making from theatre, he was part of the Indian People’s Theatre Association, and he created some landmark films during the 50s and 60’s. He struggled with alcoholism and died untimely in 1976. Of particular importance are The Cloud Capped Star (Meghe Dhaka Tara) and A River Called Titash (Titash Ekti Nodir Naam). He won awards in India and Bangladesh, but most of his films were commercially unsuccessful and he could not work the world cine circuits either. Ghatak taught at the Indian Film Institute in Pune briefly. Of late there has been a revival of interest in Ghatak’s work, and his films have finally got the acclaim they deserve.

Mrinal

Sen, like Ghatak, came to the film industry via the IPTA. His directorial debut

was commercially unsuccessful, but by his third film 22nd Sravan

(Baishey Sravan, the day Tagore died) his talent had earned him a local

reputation. His films are more ambivalent than Ray’s, often with open endings.

Sen’s work is majorly influenced by the Marxist philosophy he was exposed to in

IPTA, though his themes and subjects are wide ranging. He has won international

acclaim and awards at Cannes, Venice, Berlin, Chicago, Moscow, Montreal,

Karlovy Vary, and Cairo Film Festivals, apart from winning honorary degrees and

awards from institutions and the governments of India, France and Russia.

Other

Bengali directors such as Bimal Ray and Tapan Sinha blurred the lines between

parallel and commercial cinema in Bollywood, which itself came to be dominated

by Bengali directors such as Shakti Samanta and Hrishikesh Mukherjee in the

decades immediately after Independence. Some

of the best films from Bollywood have come from the Bengali film makers working

there – then and now (Basu Bhattacharya, Anurag Basu, Shoojit Sircar, Sujoy

Ghosh). Ditto acting performances, music direction, playback singing and cinematography.

Notable

directors who have taken parallel Bengali cinema forward after the Sen-Ghatak-Ray

trio include Gautam Ghose, Buddhadeb Bhattacharya, Anjan Dutta, Rituparna Ghosh

and several others. But quality Bengali cinema has never been restricted to

only indie, low budget arty-farty films alone. Alongside the parallel cinema

movement, there has been a steady output of robust mainstream films which have

featured great storylines, nuanced artistic performances and have been

commercially successful without the typical loud acting and crude formulas traditionally

employed by Bollywood. The first name that comes to mind here is Tarun Mazumdar

– he has made some major box office hits over a career spanning forty years.

There are several others (Salil Sen, Sudhir Mukherjee, Nirmal Dey etc).

In

fact, it is when Bengali cinema moved to blindly copy the Bollywood formula in

the 80’s and 90’s, that’s when the audiences thinned. Though the advent of

satellite TV and 24-hour channels has also impacted the film market. And since the

2000’s there has been a steady revival and an uptick in film production both quality

and volume. Here is a list of the greatest Bengali films of all time, subjective and incomplete as all such things are, but still representative of the range.

Posted for the A-Z Challenge 2019