All this month I am writing about our amazing Indian handlooms, a quick but captivating dive into the saree specifically, a garment worn by Indians for five millennia. Come with me into the magnificent, complex and utterly fascinating world of fibre and yarn, of skills and techniques of dyeing and printing and embroidery, traditions unchanged for centuries. Of sumptuous finished fabrics that not only make a fashion statement, but also constitute our cultural heritage and political identity.

Z is for Zari

|

| Zari woven motif. |

It is not known

when exactly humans discovered gold, but this shining metal has been prized for

its decorative properties from prehistorical times. The earliest known use of

gold is by the Egyptians in the fourth millennium BCE, where it was used mainly

for jewellery and ornamentation.

In India, the Rig Veda (1500 BCE) mentions Hiranya Vastra or cloth of gold, the Ramayana (500 BCE) mentions, among other things – Rama’s gold studded footwear (also a feature of the grave goods of some Egyptian Pharaohs and/or their consorts) and Sita's jewellery and garments. The Manusmriti (200 BCE) depicts Kuvera, the god of wealth, in golden garments and possessing untold amounts of the metal.

The World Gold Council estimates that Indian women hold around 11% of the worldwide gold reserves, mostly in the form of jewellery, about 24,000 MT. That's more gold than the reserves of USA, Germany and Switzerland combined. No Indian wedding is complete without some gift of gold and bridal gold-worked sarees. It’s utterly baffling when you compare the per capita GDP of the countries involved. Just saying. In short, Indian culture has a very deep history of being disproportionately fascinated with gold. Given this background, it is not at all surprising that gold (and also silver) have found their way into Indian textiles also.

|

| Benarasi Tanchoi weave. |

Zari is basically gold or metallic yarn used for embellishing textiles and Zardosi is gold embroidery. Pure zari is made by wrapping silver on a core silk yarn and gilding with gold. In modern times the silver has been replaced by copper due to cost considerations. Half fine zari uses a copper wire electroplated with silver then further gilded with gold. Tested zari is made by using a copper-silver alloy core wire which is then gilded with gold. There's imitation zari also, basically coating threads with gold coloured powders. Fast zari is made from copper with minute amounts of silver, no gold involved. Pure zari does not lose its shine. Half fine zari retains its shine longer than tested zari. Imitation and fast zari lose their shine after a few washes only.

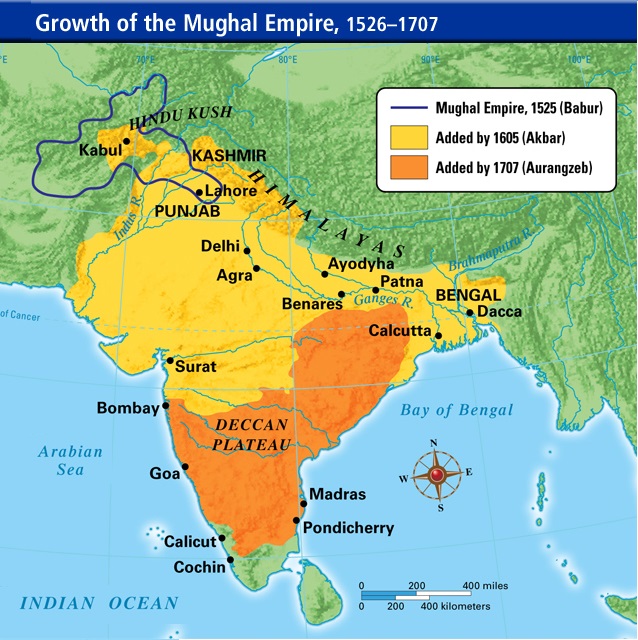

The word zari and the zardosi technique both came to India from Persia, first in the 2nd millennium BCE along the ancient silk routes. The art of zari flourished and reached its zenith under Mughal rule (1526-1857), especially under Akbar the Great (1542-1605), the third emperor of the dynasty. He brought in expert artisans from Persia and set up workshops around his empire to train local textile weavers. Except for Aurangzeb, all the subsequent rulers were great patrons of arts and culture, so textile weaving generally and zari woven Benarasis particularly reached a pinnacle during the Mughal period. Varanasi or Benaras which was a textile weaving centre for millennia, became famous for its zari worked brocades from the 16th century onwards. Of course these were restricted for the use of the elites only. The original motifs were dropped in favour of more floral and foliate Persian styles - these became an identifying characteristic of these weaves.

|

| Kadhua weave saree with close space floral/foliate or 'jangla' motif. |

We've seen other zari worked traditional sarees : the Paithani yesterday, the Kanchipuram and the Chanderi earlier in this A-Z series. Today we'll take a look at the famous Benarasi weaves.

|

| Valkalam - a more recent weave of Benarasi. |

Benarasi can be classified into different groups based on 1) the fabric (pure silk, called Katan in the trade, organza, georgette, etc., blended fabrics are a recent innovation) 2) the weaving style and motifs such as Jangla, Butidar, Tanchoi, Ektara, Valkalam, Kadhua, Phekwa, Meenakari etc. Read more about the history of Benarasi sarees in this article and see how a hand woven Benarasi saree is created in the video below:

~~~

Did you know that while Varanasi (known as Kashi in antiquity) is the centre point of Benarasi weaves, the handloom Benarasi zone includes more than a million people in Jaunpur, Gorakhpur, Chandauli, Bhadohi and Azamgarh districts?

Thank you for reading. A special vote of thanks to those who've supported this entire series. And many congrats to all A-Zers who've survived the challenge!

.jpg)